From Subjects to Citizens: How India’s Founders Risked It All on Democracy

Why India’s Founders Dared to Trust Us Before We Ever Proved Ourselves

“What would India be like if our history did not have the chapter of being a British colony?”

That’s a question I’ve been living with lately.

All these debates — did the British only loot us, or did they also ‘civilise’ us? — Carry weight only because imagining what might have been is never easy. A counterfactual is always tough to hold in the mind.

Recently, my friend Shashank Patil visited me in Banswara for five days. He’s read far more widely than I have, and studying both law and economics gives him a unique vantage. We spent long hours talking under the shade of mango trees, going on walks, or just sitting quietly, and then throwing out questions like:

— What kind of India will our generation inherit?

— What social, political, and economic challenges will confront us in the next 5-10 years — ones we simply can’t defer any longer?

— What will be our role then? How do we prepare for that one moment life gives each of us — like every general who spends years readying for the one war that defines him? How do we strategically place and prepare ourselves that when the moment arrives, we are indispensable.

One thing we both saw clearly: India will not stay the same.

Thinking about India@2047 isn’t someone else’s job — it will fall on us.

Very few of us, and I include myself here, have even begun to imagine that responsibility.

India’s Founding Moment — The Constitution of a Most Surprising Democracy

After this five-day retreat of sorts, I picked up Madhav Khosla’s book India’s Founding Moment. It felt like the perfect book at the perfect time.

Growing up, we heard stories of freedom fighters, learned a few chapters about independence in our class 6 social science books, or answered general knowledge questions like, “Who drafted the Indian Constitution?” — and proudly replied, “The Constituent Assembly chaired by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar.”

We grew up taking what we have today for granted — this right to vote, democracy itself, a basic level of economic and political freedom.

But as I read this book, it became clearer and clearer that none of this was inevitable. In fact, the odds were a hundred times higher that history could have turned out very differently.

The first part of the book is just the Introduction. And even though it truly needs to be read in full to appreciate, I couldn’t stop myself from highlighting lines and ideas that struck me. In the rest of this post, I’ll share some of those points — partly to discuss them, partly to leave them with you as food for thought.

It is doomed to fail

An Indian Parliament or collection of Indian parliaments would produce an undisguised, unqualified anarchy.

-James Fitzjames Stephen, Foundation of Government of India, 1883

The end of our Indian empire is perhaps almost as much beyond calculation as the beginning of it. There is no analogy in history either for one or the other.

- John Seeley, The Expansion of England, 1883

The British — and much of the world — were sure this was too ambitious a project to last. Honestly, I can’t even blame them.

But our founders knew the scale of the challenge. That’s why they spent so much time first acknowledging it, then finding answers.

Constitutional morality is not a natural sentiment. It has to be cultivated. We must realize that our people have yet to learn it. Democracy in India is only a top dressing on an Indian soil, which is essentially undemocratic.

- B.R. Ambedkar, Constituent Assembly Debates, 1948

Why were we doomed to fail?

At one point, I asked Shashank, “Why is it that after independence, India didn’t have a journey like the United States or Australia? Why didn’t we start afresh and build from scratch the way they did?”

And he simply said, “Because we were not virgin lands. We already had a long history, deep roots, and a sophisticated civilisation. We weren’t building on empty ground. We were rebuilding over centuries of layers.”

Western writers often saw India as a land of ceaseless conflict — or even as a place without history.

Hegel called India “stationary and fixed,” condemned by caste to “the most degrading spiritual serfdom,” with no real sense of independent life.

For him, India was a place without meaningful choice or real politics. The Indian mind was cluttered with “confused dreams,” and had none of the “intelligent, thoughtful comprehension of events” needed to shape history.

After reading Hegel’s words, I wish he were alive today to see that India lives and breathes politics. Back then, people were so suppressed, he couldn’t even spot the possibility of it.

The “slave mentality”

Nehru once said the greatest “of all the injuries done by England to India” was the creation of a “slave mentality” — a burden that left Indians psychologically unable to assert themselves.

It doesn’t even matter when Nehru said this. If you’re a middle-class Indian, you can test its truth at home.

Tell your parents you want to start a business instead of taking a secure job. Or that you want to get into politics, become a writer, take a year off to explore life — anything that doesn’t come with a neat monthly salary and steady promotions. Watch how quickly worry — and outright fear — take over.

They’ll list every risk. Remind you of family duties, “log kya kahenge,” and how one failure could ruin your life. You’ll see just how deeply we’ve been trained to think safe, small, never too wild.

When I lived in Australia for two years, the contrast was glaring. That “slave mentality” Nehru talked about? We still carry it. It’s stitched right into our DNA. And you only truly see it when you stand among people who simply don’t think that way.

The imperial state was predicated on the belief that India would have to be mediated by a superior class of people. As far as the imperialists were concerned, the only way to acquaint Indians with alien ideals was by subjecting them to political absolutism. But what were imagined to be immutable facts about Indian life were in fact the product of a certain kind of politics. A set of beliefs shaped and constructed by imperialism were assumed and rationalized as being universal truths. After all, the power of politics was precisely that it would find ways to create its own form of essentialism.

The Indian elite shared the sense that the people had to be educated. But the British had offered the wrong remedy, for the path to education lay not in the deferment of freedom and the imposition of foreign rule. Instead, it lay in the very creation of a self-sustaining democratic politics.

Nehru was indeed very optimistic:

India’s varied past demonstrated the sheer contingency of its current enslavement. Across centuries, India has shown itself to be capable of change—capable of finding new ways to survive and thrive—and it could find such ways again. …that India could be constituted and reconstituted.

The challenge

At the heart of [The Indian founding] moment—…lay the question of democracy in an environment unqualified for its existence. Democracy was being instituted in a difficult setting: poor and illiterate, divided by caste, religion, and language, and burdened by centuries of tradition.

In the West, the historical path of countries saw improvements in prosperity, stronger administration systems, and the subsequent extension of the franchise. Universal suffrage came after a reasonable average level of income had been secured and state administrative systems were relatively well established.

The immediate coming of universal suffrage in India’s settings is even more arresting. … The First World War had brushed aside the major continental empires only to create democratic states that readily collapsed in the 1920s and 1930s. … “Popular government,” the prominent British scholar and politician James Bryce wrote in 1921, “has not yet been proved to guarantee, always and everywhere, good government.”

At that time, the West openly told Indians that democracy wasn’t meant for them. In 1949, British Prime Minister Clement Attlee even wrote to Nehru, saying that monarchy suited Asian countries better. He argued that India’s own history favored kings, while ideas like a republic were foreign imports from Europe, understood only by a small educated class. According to him, the few Asian republics that existed didn’t do well — they often ended up as dictatorships, run by power-hungry leaders.

Philip Spratt, a British thinker and activist, once said that the Indian Constitution “is basically a liberal constitution forced on a society that isn’t liberal, and so you can’t expect it to work.”

You’d probably agree with the first part of what he said every morning just by reading the Indian Express or Dainik Bhaskar. But the second part? Our still-thriving, slowly maturing democracy proves him wrong every single day.

A place like India was lacking in many of Britain’s renowned features: a basic standard of education and literacy; and broad homogeneity in class, language, and religion.

It is striking that even in 1956, Jennings felt that the question of suffrage should remain open. When a country came to decide on suffrage, it would do well to remember that “it may be possible to minimize the risks by creating a limited franchise or by balancing representation.”

The Report on Indian Constitutional Reforms of 1918 stated that India’s people were poor and incapable, and they belonged to a society that was without solidarity. … India may well find itself ready for some future occasion, but that day had not yet arrived.

The Indian Solution

When you study the vision behind our Constitution, you see the kind of political system our founders believed could handle the huge challenge of turning India into a democracy. This system rested on three main ideas: the explication of rules through codification; the existence of an overarching state; and representation centred on individuals.

As an economics student, I’ve often questioned this heavy centralization of power in India. I’ve compared the limited powers of our city municipal councils with the far greater powers of city governments in places like New York or London. Like many of us, I’ve written and spoken plenty about the virtues of decentralization.

The choice of a strong centralized state was hardly a self-evident one. Indian intellectual history had a long tradition of local government thought, and several proposals for the reconstruction of India drew on this tradition. The contest over centralization, we shall find, was a contest between the state and society.

But reading this book gave me a new perspective. I now see that the very reason we can debate more decentralization today is because our founders already grappled with this question in their own time. They chose what they felt was needed, then — to keep this vast, diverse country together — and because of that choice, we have reached a point where we can now safely argue for more local power. We’ve survived and strengthened our democracy enough to do so.

Supporters of a strong centralized state did not trust that Indian society had the internal capacity for order and change. Their conception of Indian society made the centrality of the state inevitable.

The founders believed that a centralized state was the only mechanism that could stand above all other forces and restructure the relationship among those it governed.

because municipal structures- governmental and nongovernmental alike-were thought to be captured by rigid social and cultural bonds and prejudices.

India's awesome diversity was routinely referenced as a reason for its incompatibility with self-government.

Centralization could liberate a society seized by local antidemocratic sentiments, and a theory of representation unmediated by forced identities could meet the challenges of difference.

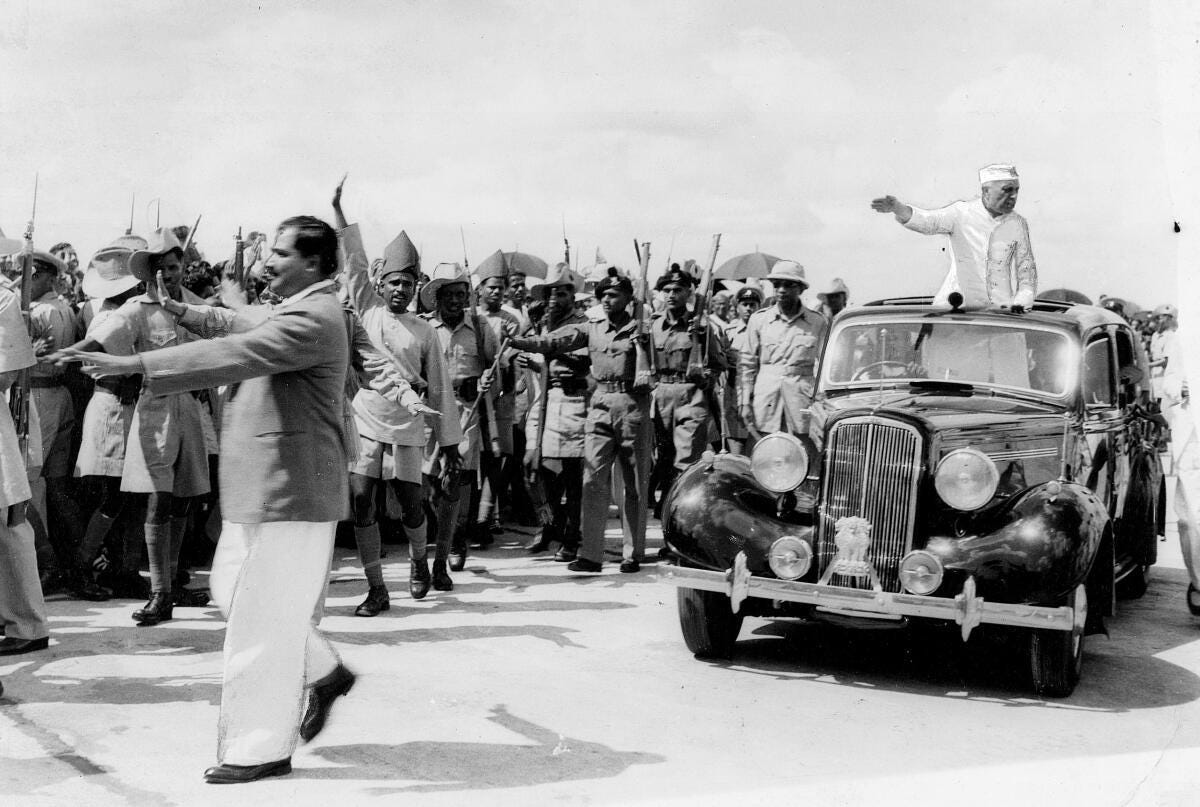

“Converting Indians from subjects to citizens.”— CANNOT THINK OF A BETTER LINE.

Democracy was interpreted not as a sum of performances, but as a form of government where behavior had a common meaning. The rules and structures and institutions were efforts not only to shape action but, more fundamentally, to provide meaning to practices that could be shared. … to realise this —converting Indians from subjects to citizens.

The challenge and determination for the Universal Adult Franchise

When Indians turned to the suffrage question in the nineteenth century, their agenda was greater involvement in the colonial administration. In the twentieth century, … concern over the internal distribution of power declined as national sovereignty became the goal.

The Motilal Nehru Report of 1928 committed India to universal franchise. It argued that the very exercise of the right to vote was a form of education.

Gandhi Ji declared in 1939 that he was unworried by illiteracy and “would plump for unadulterated adult franchise for both men and women.”

Qualifications based on education and property during colonial rule meant the de facto exclusion of the lower castes.

"The success of democracy depends on the response of the voters to the opportunities given to them. But, conversely, the opportunities must be given in order to call forth that response. The exercise of popular government is itself an education... enfranchisement itself may be precisely the stimulus needed to awaken interest."

To limit the suffrage on account of illiteracy was a kind of perversity, because literacy had first been denied to a segment of the population, and now that segment was being denied suffrage because it was illiterate.

Read the above two quotes again. They’re worth it.

To limit the franchise, Ambedkar believed, was to misunderstand the meaning of democracy. It was to proclaim that democracy was solely about the expression of preferences at the ballot box. Instead of falling prey to this vision, which he saw as impoverished, Ambedkar turned to John Dewey to underline the relationship between democracy and participation. Dewey had regarded a democratic society as entailing more than a specific kind of government. At a deeper level, what such a society offered was "a mode of associated living, of conjoint communicated experience." A democracy involves many different avenues of shared interest among its people. This sharing meant that one always had to consider the actions of others, just as the actions of others informed how one chose to act. Such a process meant the end of isolation. One had to react to a world that possessed far greater variety— this process led to progress and released a great number of capacities that prior forms of narrow behavior had curbed. It is easy to see why Ambedkar found this account compelling.

Gandhi's draft resolution in 1940 declared that the "people of India alone can properly shape their own constitution and determine their relations to other countries of the world, through a constituent assembly elected on the basis of adult suffrage."

In today’s India, with so much money and machinery at our disposal, we hardly even think about the logistics of organising events — even massive ones like elections. It’s all taken for granted.

But when I read the following statement, I truly appreciated how far we’ve come.

Prasad, the President of the Constituent Assembly, admitted that “the mere act of printing [the electoral roll] is such a big and tremendous job that the governments are being hard put to it, to find the presses which will undertake this big job.”

For many members back then, choosing universal adult franchise wasn’t just a democratic ideal — it was an act of real courage.

Some Food for Thought

British rule in India remained what James Fitzjames Stephen once described as "an absolute government, founded not on consent but on conquest."

A recent meditation on global democracy put the matter plainly when it recognized that India is "the most surprising democracy there has ever been: surprising in its scale, in its persistence among a huge and, for most of its existence, still exceedingly poor population, and in its tensile strength in the face of fierce centrifugal pressures and high levels of violence, corruption, and human oppression throughout most of its existence.”

The Architecture of democracy

creation of a democratic citizen. A feature of this conception was that popular authorization-that is, the exercise of the vote-was necessary but insufficient for a political system to have legitimate authority.

One must ask not merely what kind of postcolonial structure was conceptualized by India's founders but also how such a structure was seen as validating the use of authority and legitimizing the application of coercive power. This question matters in all constitutional democracies, but it might be a salient one for those that involve radical transformations.

Rousseau says that freedom turns not only on our consent but also on the conditions that our consent engenders. It is not enough to assert that democracy has moral force because it allows for all to participate equally. More is usually required for us to accept the law's claim to authority and its exercise of coercive power.

The founding schema had features that we would associate with contemporary liberal thought: it committed itself to a common language of the rule of law, executed through codification; it constructed a centralized state and rejected localism; and it instituted a model of representation whose units were individuals rather than groups.

The text was conceived not simply as a means to enable or prohibit action but as a device that could define the nature of political actions and the concepts that such actions implicated.

It would be an instrument of political education-aspiring to nothing short of building a new civic culture.

The codification of rules was one way to liberate Indians from existing forms of thought and understanding.

Codification could serve an educational role in a country without established constitutional conventions.

The codification of norms, the existence of a centralized state, and the freedom from communal groupings would allow Indians to engage in a new form of reasoning and participation. Each was a path to the creation of a polity. Together, the different mechanisms could produce democratic citizens.

The introduction of popular authorization, the creation of rules constituting public authority and participation, the concentration of authority in the state, the identification of self-determination with individual freedom, and the separation of the public and the private emerged at a single moment. The moment was a historical response to both eighteenth-century failures and nineteenth-century critics of democracy.

The fears in the Indian case were not altogether different from those in the West: the unraveling of social harmony; the unintelligent and irresponsible exercise of the right to vote; the exploitation of power by those elected to office; the lack of enforcement of a political mandate; and above all the misuse of public power.

When I look at this journey — from being a land doubted by its rulers, to crafting a Constitution that dared to trust its poorest, most diverse people with power — I’m struck by how audacious it all was. Even more remarkable is that, despite every flaw, every stumble, India’s democracy has held. It is still teaching us, still shaping us, still demanding we grow into the citizens our founders once only hoped we could become. Perhaps the real work now is to keep earning that trust they placed in us — and to imagine, with the same fearless clarity, what kind of India we want to hand over in 2047.